George Saunders has a startling mind. It slides off the everyday and shows it slantwise, letting us see ourselves afresh.

Saunders, said in The New Yorker recently: ‘What I am trying to do these days, in the story form, is surprise myself – get out beyond my conscious mind and what I already believe and perform a sort of rowdy, joyful blurt.’

His work is indeed joyful. My looking-at-the-world-slantwise muscles are woefully atrophied. Reading Saunders was like discovering I was allowed to learn to fly (and I don’t mean get my pilot license).

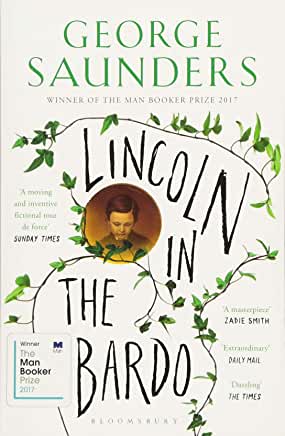

My latest literary crush began in November, about three lines into Ghoul. I immediately invested in the short story collection Tenth of December, which didn’t disappoint, and then made my way to the 2017 Booker prize winner, his only novel to date, Lincoln in the Bardo.

It has a reputation as a challenging read and it certainly does ask the reader to pay attention. There are multiple (dead) narrators, and their contributions are laid out like quotes from books, interspersed with ‘real’ quotes from books (though I suspect they are fictional books). Is this meta enough for you yet? I decided to not worry about who said what, just let the story take me and check back later if need be, and this worked well.

The dead unwell folks in their coffins sick boxes in the cemetery are disturbed that their newest member, a boy, intends to stay: he’s sure his father will be back to see him. The boy smells unpleasantly of spring onions so they would rather he moved on (they are also aware that if he lingers then he will suffer, but they’d rather talk about the smell). Other sources inform us that this boy is Willie, son of President Lincoln. Lincoln is devastated by his son’s death, and that night he pays his son a visit.

There are a plethora of characters in this novel, all fighting to be heard, each with their own stories to tell, their own view of history and of each other. Anecdotes, layered upon observations, layered upon opinions. Deeply personal first person testaments gather and combine to give us a history of America. It is extremely moving.

It is also extremely funny. The character’s have many idiosyncrasies, revealed in their appearance and their language – the book is Dickensian in its attention to detail. Some provide light relief – like the bachelors who fly in the air and throw a blizzard of hats down to indicate their mood. It is apparent that the mind behind the book likes to play.

Storr (https://thescienceofstorytelling.com – there’s a book on Amazon as well) talks about how readers like a mystery to solve (now I’m channeling Scooby Doo – see, more playful already). Saunders piques our curiosity again and again as he pushes the narrative forward. Why haven’t these people ascended? Why do they take the forms that they take? Can they influence Lincoln and – most urgently – will they be able to save the boy?

My main takeaway is that Saunders isn’t afraid to play with form, and indeed play generally, but that he does so from a strong base of traditional story telling – strongly defined characters and a compelling sense of forward motion that keeps us turning those pages. It thoroughly deserves the prizes.

Have you read this book? What did you think? I’d love to know,